I walked into Gulu Women’s Prison for the last time carrying the pleasing combination of several poetry books and one hacksaw. No one checked my bag. They never have.

The poetry books were for the library, which is now installed in the ‘office’ (corrugated iron shed).

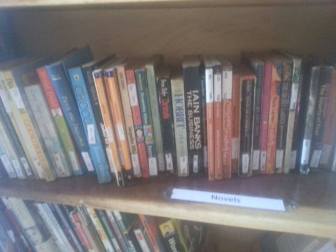

Librarian Irene, who also shared her story in our book, with the new library shelves. This is the one and only photograph I’ve been allowed to take inside the prison.

The hacksaw was to saw through the padlock on a large metal locked box which I’m told was left here by another mzungu (foreigner) a long time ago. She came once a week to have play sessions with the children who live in the prison and kept toys in the box. I have been asking for months where the key is. I wanted children to use the toys. And it didn’t feel like the box was full, so I also wanted it for stationery storage. The key had been left with a guard, who had either lost it or just wasn’t motivated enough to find it for us, or maybe feared being exposed for stealing some of the box’s contents.

This box had been a cautionary tale to me, and has fuelled efforts to pass the torch of the women’s education programme on to other individuals and organizations, leave detailed information about everything we have done, and leave keys with three different people, none of whom are guards.

We liberated the toys, and filled the box with exercise books, chalk, and pens.

The women are very happy about the library, and want to convey thanks to everyone who donated to the book project. While a large number of books are borrowed from the men’s library, the shelves, phonics readers, and a full set of curriculum books was purchased, along with a large supply of stationery, with funds raised by the women’s

The arrival of a full set of curriculum books for the teachers, bought with funds raised by their stories.

stories and poems.

While moving things about in the office, I also discovered a disconcerting number of bras.

‘Who takes their bras off in the office?’ I joked. I was wondering if perhaps they had been donated and the guards needed a nudge to distribute them.

‘They are ours,’ Irene said, ‘We are not allowed to wear them.’

‘Why not?’

‘To discourage escape. It’s painful to run with no bra, you know?’

Self-help books chosen by the women from the main library. A notable focus on starting small businesses.

Gah.

On a brighter note, the first books signed out of the library were: Things Fall Apart, Fix your self-esteem, Giraffes can’t dance (a children’s book), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, poems by Mary Oliver, and ‘Learn about Russia!’ Happy days.

But then, amid celebration over the library, and the fact that the education programme had run smoothly without my having to lobby the guards for over a week, something happened.

A woman had escaped two days ago, running away from her work gang and into the

The novel selection. I’ve arranged for someone to swap these for new ones from the abundant men’s library every couple of months so women get a fresh supply.

bush when a guard’s back was turned. Her husband spotted her hiding near their village and called the police (almost certainly paying them a bribe to come and get her).

‘Why did her husband turn her in?’

‘He hates her. That is why she is here in the first place. He took her to court for charges of child neglect because she wanted to leave him but couldn’t look after the baby so she tried to leave it with his family.’

Other prisoners carried the woman into the prison, and I was shocked to see them slapping her, hard, about the head as they did so. She was left lying, crying, on the ground. I was sitting in a meeting with the welfare officer, teachers and students, and it was clear from everyone’s behaviour that while they would briefly turn to watch, they expected the meeting to continue like normal.

The Overall In-Charge of the women’s prison, a large guard with braids pulled back into a tight bun, walked over to the woman on the ground and started kicking her. Then, guards dragged her into the shed, and we could hear the sounds of her being beaten. She screamed and screamed.

Children’s books are very handy for the new readers.

I froze up and didn’t do anything and the meeting continued. In all likelihood, my protest only would have delayed the beating. But I still think intervening was the right thing to do and I am ashamed that I didn’t do it.

It strikes me that this is why people pray, or meditate, or whatever, every day. Not because they struggle to remember in thought what is right and good but because doing what is right in an unexpected situation, against social expectation, is so hard (for most of us) that you must have your conviction wrapped around your very bones. You must have to train the pursuit of justice into yourself until it is an automatic reaction stronger than fear or

The non-fiction section. We were able to meet requests for ‘books with pictures of other countries’ and ‘a book about ghosts’.

social conformity.

The screaming stopped. I wished I was 1) not a coward 2) staying forever, and 3) some kind of lawyer, not a teacher. I went into the office/shed on some excuse and found the woman sitting upright, though limply, against the new bookshelves. She was bleeding in several places and her eyes looked blank. There were bits of broken sticks all over the floor. I was worried she had a concussion or other dangerous injury so I asked if they hit her head. She said no, they only slapped her face and the heavy beating was all on her limbs. She seemed exhausted, more than anything else.

There is one NGO I know of in Gulu which helps with a small number of court cases, trying to get justice for prisoners, though their size and presence is such that they’re not working on any of the wrongful convictions I know about, and I’ve never seen them in the women’s prison. I don’t know of any who advocate for the treatment of prisoners in prisons, and the idea that the government prison system itself might care and try to protect prisoners feels laughable.

This is the library shelf. Beside it is a second shelf full of teacher resources.

So it was a very mixed ending. I feel positive about the continuation of education and reading for women in the prison. But the sight of the beaten and bloodied woman, who had in all likelihood only done what she thought best for her child in a very desperate situation, leaning against the bookshelves, was a stark reminder of the reality of prison life here.

Pastor Florence was not there when the beating took place, but soon arrived to pray with the woman and comfort her with her own story, from the worst depths of prison violence and injustice, to the hope of a free and happy life.